“To fail to resist is to be complicit.” —Father Frank Alagna, cofounder of the Ulster Immigrant Defense Network

One morning in early December 2016, Father Frank Alagna had a disturbing epiphany. The 74-year-old Episcopal priest had just finished presiding over the Spanish-language mass at Holy Cross/Santa Cruz in Midtown Kingston, the bilingual church where he has been priest-in-charge for the past decade.

Nearly three years later, sitting in the rectory behind the cathedral, Alagna’s voice shakes and his eyes well with emotion as he recalls that day. “I’m sorry. It makes me so angry,” he says as he clears his throat and wipes his face with the back of his hand. “I had to tell my congregants, Latino congregants, people who I care so much about, and people I could see were profoundly afraid, of an urgent need.” Alagna explains that he had to warn parents that they must get legal documents giving friends or other family members custody of their children in case they were detained by ICE. “I have never had such a horrible experience in my 48 years as a priest, having to communicate this kind of reality.”

Today Alagna is one of several leaders in the Hudson Valley who are fighting back against what they view as unjust federal policies targeting immigrants. He heads what has become the Ulster Immigrant Defense Network, which is a consortium of groups including Nobody Leaves Mid-Hudson, the Worker Justice Center, Rural & Migrant Ministry, and others. UIDN runs multiple workshops for attendees from both sides of the river, with specific programs, such as helping undocumented students and their teachers know how to get the most from their education, and broader outreach ranging from understanding rights as workers to how to get access to healthcare.

UIDN is hardly alone. Other grassroots organizations, such as the Columbia County Sanctuary Movement, have also sprung to life, providing pragmatic help to immigrants mostly based in and around the city of Hudson, such as rides to doctor’s appointments or advice about housing.

Meanwhile, existing nonprofits, such as Catholic Charities and the Worker Justice Center, have both grown in their strength and influence across the Hudson Valley. Catholic Charities is bolstering its roster of attorneys providing pro-bono legal advice, while Worker Justice successfully advocated in Albany for legislation such as the Green Light Bill, which lets people without a social security number apply for a driver’s license, register a car, and—crucially for the safety of all drivers, according to a 2018 study by AAA—obtain car insurance. Worker Justice also pushed for passage of the Farmworkers Fair Labor Practices Act, which guarantees a right to work no more than 60 hours per week, and a right to have at least one day off a week.

Light in the Darkness

Much of this action came as a counterweight to Donald Trump. Though Mariel Fiori, founder of La Voz magazine in 2004, laughs when she says that there were “woke white people when I participated in my first immigration march in 2006.” Fiori, who immigrated from Argentina two decades ago, notes that Latinos had been marginalized long before 2016, and even if it took this administration to wake up more community members in the region, she’s profoundly heartened by what she’s witnessed. For instance, she says, “Jewish people really came out strong. They saw what happened in the Holocaust and persecution of Latinos touches them very deeply.”

Alagna agrees, and notes that as a first step, right after Trump was elected, he reached out to Muslim, Jewish, and other Christian sects in Kingston and beyond and got 21 regional clergy to petition the Kingston Common Council and the mayor to help push the town to become a sanctuary city.

It was merely symbolic, Alagna admits.

Sanctuary for a city is conceptual, and even as New York State’s Supreme Court ruled last year that local police cannot detain ICE suspects and that jails cannot hold someone beyond when they would ordinarily be released, an Albany Times Union report this past spring found it’s routine for police in the Capital Region to inquire about immigration status when pulling over drivers for minor infractions—or for no probable cause whatsoever. Preventing local cops or administrators from helping ICE is beyond the jurisdiction of cities, and can only be enshrined by state legislation, which is currently pending.

Which leaves it to private citizens to act, Alagna says. “Jesus says to help the least of our brethren, whatever form they come in.”

But what does sanctuary look like? “I had in mind this Hunchback of Notre Dame model, of literal sanctuary in our places of worship,” he says, but once UIDN began, with a hastily convened meeting in February 2017, where Alagna was expecting about 20 volunteers and 120 people showed up at his church, his vision grew. “I realized we could build something far more comprehensive. All that energy,” Alagna says of UIDN’s small army of volunteers, “was the grace. The light to be found in this darkness.”

The Regional Economy and Immigration

Forget Alagna’s sentiment. If you live in the Hudson Valley, what does this attack on immigration mean for our tax base, and for the local economy?

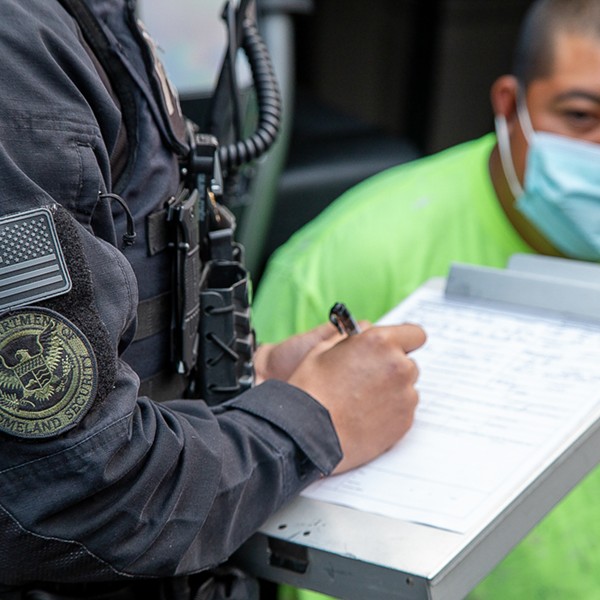

From 2017 to the fall of 2019, the Trump administration has instituted a broad crackdown on immigrants, documented as well as undocumented, according to Syracuse University’s massive database (TRAC) that quantifies and counts arrests, incarcerations, and deportations. Since Trump took office, new court filings to begin deportation proceedings have spiked: They were up 23 percent to 340,000 last year, and 2019 will easily crest 400,000. At that pace, 2019 enforcement will be 50 percent higher than it was in 2016.

Regionally, ICE has heavily targeted people coming in and out of courthouses, or appearing to testify on behalf of defendants on trial, with arrests up 1,700 percent since 2016 through 2018, according to an early 2019 report by the Immigrant Defense Project. This is a policy that a regional ICE official, Thomas Decker, defended recently, saying ICE is targeting felons.

However, Syracuse’s TRAC shows that despite Trump’s repeated rhetoric of going after gang members, through June 2019, arrests of immigrants with criminal records is a minuscule 2.8 percent, compared with over 16 percent a decade ago, and 25 percent back in 1999. Locally and nationally, ICE is arresting mostly non-criminals, and, as was detailed in a recent New York Times Magazine piece, ICE is armed with high-tech tools to track people and deceptive tactics to apprehend them. A July 25 piece in The Intercept shines a bright light on these practices. And you can see exactly how ICE works by using New York’s Immigrant Defense Project web tool, which highlights most of ICE’s busts in the region dating back to 2013, as well as how frequently agents lied about their identity, used fake Facebook ID’s, and pretended to be contractors hiring workers.

If all the above is simply carrying out the law, the result is straining the regional economy.

According to a 2017 Fiscal Policy Institute Study, there are roughly 105,000 undocumented immigrants over the age of 16 in the region, generating $3.4 billion in spending power and $1.5 billion in taxes, according to New American Economy’s estimate of the 18th and 19th Congressional districts.

That economic engine is stalling, however, because the Brookings Institution finds that the foreign-born population in the US in 2017-2018 grew by only 203,000, the slowest rate since 2007, while they also find that the native-born birthrate is at an 80-year low. An economy withers without workers, and another study by Brookings found that the nation is on the cusp of having more seniors than children for the first time in 240 years. According to a 2019 report by the Economic Innovation Group (EIC), we live at ground zero for this crisis, with some of the weakest population growth in the nation across the Hudson Valley. EIC suggests nothing short of the exact opposite of Trump’s policies, vouching to bring in vastly more foreign-born workers to rural areas to reverse this slide, because, for the most part, in addition to a zero or negative birthrate, young people are fleeing rural America at an accelerating pace.

The Face of Advocacy

Meanwhile there are at least 100,000 immigrants in the Hudson Valley already, and some Americans are choosing to help them. But every one of those advocates’ stories is different.

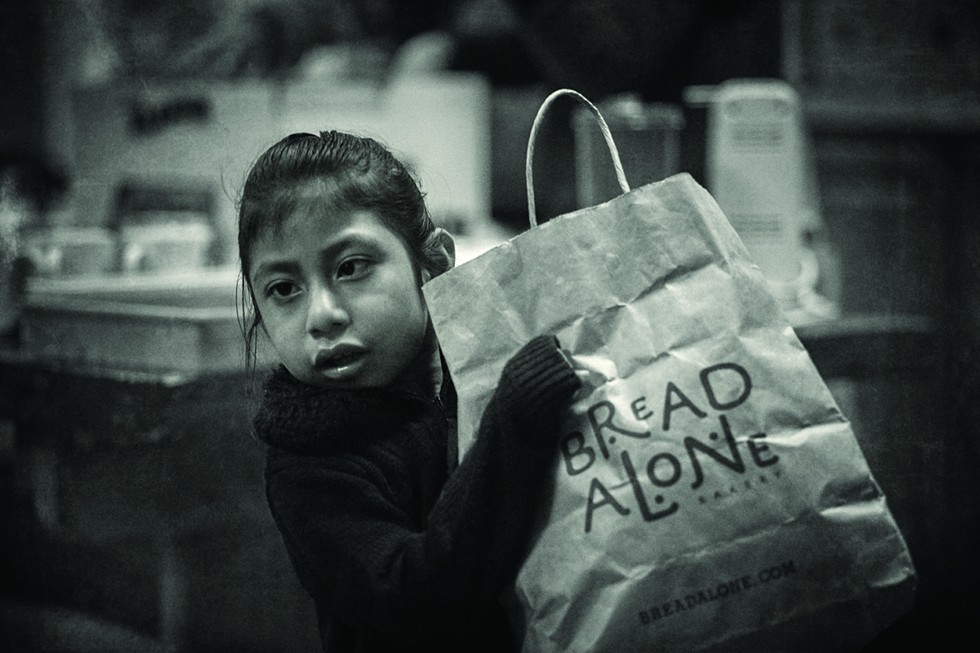

“Coming to the United States wasn’t a dream,” recalls Cecilia Cortina Segovia, a human trafficking specialist at the Worker Justice Center in Kingston. “In fact, it was more like a necessity.” When gang violence erupted in Baja California, where she was working with her American-born husband as an outreach manager to establish an urban farming coalition in the city of La Paz, they decided they had to flee north. “One day we were listening to the gunshots outside the house. We heard them every single night. And I was holding my nine-month-old baby. I had to do what was best for him,” says Segovia.

Segovia was born in Mexico. But she isn’t the stereotypical penniless migrant displayed on TV. Fiori of La Voz says too often there’s an immediate air of pity, or spite, against Latinx immigrants, and an expectation that every immigrant is poor and uneducated. “We are individuals. We are not a monolith. Some of us came here with PhDs.” Fiori notes that advocates like Segovia, who has a bachelor’s in educational communication and has a history working for nonprofits, is the face of something more nuanced. “Thanks to Mr. Trump, more white people are woke to what’s going on. But what’s important now is agency—the Latinx community is advocating for itself.”

For Segovia, that translated to continuing the kind of battle she waged in Mexico, helping to push for social justice. “When I immigrated in 2014, I was amazed—and not in a good way—even as someone with a decent understanding of English, of how hard this process was. I couldn’t imagine someone who doesn’t speak the language navigating the paperwork.” Segovia began volunteering with Worker Justice in 2015, which has offices in Rochester, Kingston, and Hawthorne and fights against wage theft among blue collar workers in fields such as farming and restaurant jobs.

Now, as an expert in human trafficking, she says that it’s mostly not cases of prostitution, but something more like slavery. She cited a current case in which a restaurant worker in the lower Hudson Valley was recruited and smuggled to the US, then forced to work long hours with low pay, and to shell out for his lodging. Eventually, when he got hurt on the job, his boss threatened to turn him over to immigration.

Segovia says while current New York State law helps somewhat, the problem is at the federal level.

She cites a 2014 Urban Institute study which shows that in 71 percent of the cases of human trafficking, the victim entered the US on a legal visa. “They come legally,” Segovia emphasizes.

But she says victims often have no network when they arrive—they only know the trafficker and the promise of a making a quick buck for the duration of their visa, and even if they’re in the US legally, they’re highly vulnerable. And, Segovia explains, too often they’re encouraged to overstay their visas, “And the trafficker says, ‘Don’t worry, I’ll take care of it,’ but does nothing.”

Now the victims have become undocumented and are further enslaved to the trafficker, afraid to report the crime and expose themselves. In the present environment, these victims are going to stay cowering in the shadows, she says.

Victor Cueva, an attorney with Catholic Charities, sees these kinds of cases all too frequently, and he says despite the rhetoric, the Trump administration is making protecting other immigrants, especially women who are victims of domestic violence, far harder. In September, Cueva was working on gaining asylum for one of his clients, who was the target of sexual assault. But in July, the Justice Department overturned existing precedent that had protected family members who were targeted as a group, and last year a similar law that protected victims of sexual predation was also overturned.

Cueva, 30, works throughout the Hudson Valley. He says that the Trump Administration is constantly trying to make the job of helping immigrants harder. He has one client whose undocumented husband cannot speak on her behalf, for fear of showing up at court, even though he has powerful testimony that could help his client’s case. Cueva notes that even veterans and active-duty military are under assault by Trump’s actions. One lesser-known policy, parole in place, was designed so that veterans and military who’d married immigrants wouldn’t have to worry during deployment about their spouses going through legal immigration paperwork. But Trump is abolishing the program, which luckily Cueva heard about in time to expedite a green card for the spouse of a military client. “This was someone who fought in Iraq. You’d think we’d want to keep this law.”

A Knock at the Door

While Cueva and Segovia work on specific administrative remedies, and Alagna’s day to day seems to focus on concrete needs, such as shelter, frequently advocacy takes the form of triage—like throwing your body at the barricades.

Gloria Martinez, 29, and Bryan MacCormack, 30, are co-founders, along with Juan Basilio Sanchez, and his son Juan Simon Sanchez, of the tiny Columbia County Sanctuary Movement. Martinez says the four founded CCSM “because there was really nothing like this in our community in Hudson,” and because despite having temporary protected status as the victim of domestic violence and a refugee of the Salvadoran Civil War, Martinez’s mother was repeatedly threatened by immigration officers who said that they would deport her.

Such threats were hardly idle; Martinez’s uncle was deported in 2017. Then, on March 5 of this year, ICE agents tried to arrest two undocumented immigrants in MacCormack’s car as he drove them from an appointment at Hudson City Court.

But MacCormack, who’d been studying the law as part of know-your-rights training he and other CCSM volunteers have been teaching to migrants, was well aware that the ICE agents didn’t have a judicial warrant signed by a judge. The cell phone video of that day, where MacCormack calmly tells ICE officials that his lawyer is on the way and that they don’t have a right to search the car or to arrest him or his passengers, went viral and was seen over 50 million times worldwide. It galvanized support for CCSM, Martinez says, and while she doesn’t only want the organization to be known for that one bold act of resistance, she notes that it was crucial for spreading the message that everyone has rights and that they have to know what they are.

Green Shoots

Even in the face of what Father Alagna sees as gross injustice, there’s hope. UIDN regularly packs workshops with participants from as far south as Rockland and up to Greene County. And he mentions something that echoes Cueva’s perspective, even though Cueva is a recent immigrant and Alagna was born in the US: “We’re always learning,” Alagna says. “We want to help, but we have to have our ears open to know how.”

Mariel Fiori of La Voz says to achieve that mission, these groups need to incorporate more people like Cueva. “There’s this catchphrase of ‘diversity and inclusion.’ Diversity is when you get invited to the party. Inclusion is when you decide it’s your party.”

Cueva is pleased to be the face of immigrants advocating on their own behalf, but what he sees as just as important is that his other community, of lawyers, understands and wants to help undocumented and documented immigrants. Cueva graduated from a program called the Immigrant Justice Corps (IJC), a national organization that provides legal services to immigrant families. His class was the first to expand services to the Hudson Valley. “Now we’re rolling out nationwide,” Cueva says. “Something that started here is going to spread across the country, and there’s this fellowship and it’s super competitive, with lawyers from the top law schools that are hand-picked.” Cueva explains that he’s also spearheading a complementary effort to recruit retired attorneys and pro-bono lawyers who don’t know immigration law but want to help. And he has peers doing identical IJC recruiting in Westchester and in Albany. “We’re going to be able to provide immigration representation in places that have never had it, from Sullivan up to Greene counties,” Cueva says. “We want to provide this service because there are so many people who need help and have never known how to even ask for it.”

Even so, CCSM’s Gloria Martinez says there’s a constant struggle to pay the bills, and that raising money for advocacy and applying for grants is daunting. Most of the organizations profiled here rely heavily on private and grant funding. Alagna says UIDN’s already spent over $30,000 in 2019 on transportation costs alone.

But Alagna, along with everyone interviewed for this story, noted that the backbone of each one of these organizations isn’t just check writers, but people willing to donate time. “I was sitting with a group of volunteers,” he says, recounting one evening two years ago, early in UIDN’s formation. “I asked everyone why they wanted to help.” He went around the room and some Christians mentioned Jesus’s teachings. Some Jews said it was their turn to give back to non-Jews who put their lives on the line during the Holocaust. “And others who identified with no faith said this is what it means to be a good human being,” Alagna says. “I’m the one whose job it is to say what it means to be holy, and it dawns on me they’re teaching me what holiness means.” Alagna adds that his own conscience tells him that in times of crisis failing to act is to be complicit in the crime.

Members of all four advocacy groups say that they see resistance in both large and small ways throughout the region. Alagna smiles and acknowledges the broad upwelling of support. “We’re learning what it means to be a community, we’re learning who our neighbors are, and we’re opening our hearts to what it means, regardless of religion or no religion, to help each other.”

This article was published in the November 2019 issue of Chronogram.