The Facebook posts came frequently, sometimes as many as a half-dozen per day. They included material that was inflammatory, racist, proudly inciting of violence, and in many cases, untrue. And they were posted to the personal Facebook page of Ryan Griffin, a deputy in the Dutchess County Sheriff’s Office and the president of the department’s Police Benevolent Association, a powerful police union.

In the weeks leading up to the presidential election, Griffin shared posts attacking Joe Biden with unsubstantiated claims or crude imagery. One read: “Biden’s not the enemy waiting to attack us from within. He’s the hollowed out, wooden horse they’re using to sneak through our gates.” Another warned that “Civil War is coming be ready.” In the comments of another post on Griffin’s page, a Facebook friend posted an edited image that depicts Kamala Harris in a sexual act.

After the election, Griffin shared a post calling into question the results, and one promoting the QAnon conspiracy theory, which alleges that a secret cabal of Satanic pedophiles is running a global child sex-trafficking ring, and that Donald Trump is working to stop them.

Other targets of Griffin’s posts were closer to home. “This is what those left wing democrats who are in our very own City of Poughkeepsie Government support in regards to BLM; Sarah A. Salem. Look her up and vote her out. Or, write to our liberal governor to have her removed,” Griffin wrote after sharing an article from the right-wing publication Law Enforcement Today, which accused a bystander of being “gleeful” and laughing after two police officers were shot. “Let me know how that works out…” he concluded. (Salem chairs the Poughkeepsie Common Council and is an outspoken supporter of Black Lives Matter).

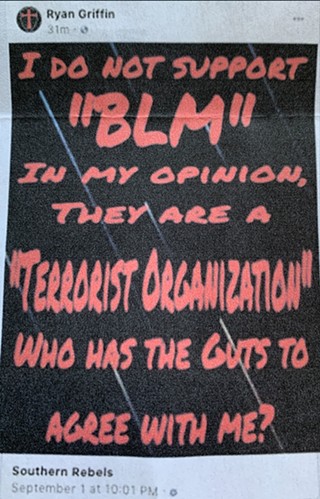

Black Lives Matter was a frequent target of Griffin. “I do not support ‘BLM.’ In my opinion, they are a ‘terrorist organization,’” reads another post he shared, from a group called Southern Rebels. “Who has the guts to agree with me?” In another, Griffin shared a photo of a Black Lives Matter flag and a pride flag hanging in a school classroom. “If God isn’t allowed in schools,” he wrote, “this shouldn’t be either.”

Griffin’s profile photo at the time was the Knights Templar cross, which has been adopted by white supremacist groups and conspiracy theorists, including at the 2017 Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia.

Reached for comment by The River, a spokesperson for the Dutchess County Sheriff’s Office said via email that “this matter is being taken seriously and is under investigation by this Office.” Griffin’s Facebook page, which had been public, soon vanished from the platform.

According to the spokesperson, Captain John Watterson, the Sheriff’s Office conducted an Internal Affairs investigation after being contacted by The River. The results of that investigation were forwarded for administrative review in mid-December, which would determine if and how Griffin would be disciplined for the posts.

“Sheriff [Butch] Anderson takes this issue extremely seriously, and the matter will be dealt with appropriately once all of the facts have been assessed,” Watterson said, noting that Griffin was assigned to an administrative unit that does not have contact with the public. “Bias has no place at the Dutchess County Sheriff’s Office and will not be tolerated in any form.”

Watterson would not put a timeline on when that assessment would be complete, however, writing that “the Internal Affairs/disciplinary process can vary depending on the case.” The River has checked in periodically with Watterson since then, but as of Friday, March 5, “there are no updates with respect to the investigation.”

Griffin provided a written statement to The River, as well, which offered a free speech defense. “The posts in question were not my original content and were not meant to be inflammatory or discriminatory, but rather an expression of diversity,” he wrote. “I believe everyone is entitled to their opinion and has the right to express their views freely without fear of being treated unequally. Due to this belief, I must apologize to anyone who viewed this content and concluded that I may be intolerant or biased in any way.

“As a Deputy Sheriff and the President of the PBA I can appreciate your inquiry and assure you that I am sympathetic to the issues we are all facing. The most important thing to me is that I maintain the trust of my community and the respect of the people I serve. It is important now, more than ever before, that we function as one so we can begin healing as a nation.”

A Reckoning for Local Law Enforcement

The inquiry into Griffin’s social media activity is happening amid heightened scrutiny of the connections between law enforcement and extremism. The problem is particularly acute in local police departments, which have less stringent oversight than the military or federal law enforcement.

A report published in August by the Brennan Center for Justice, a law and public policy institute, titled “Hidden in Plain Sight: Racism, White Supremacy, and Far-Right Militancy in Law Enforcement,” detailed how racial disparities in the criminal justice process and personal prejudice among officers often reinforce each other in a vicious feedback loop. One problem with rooting out bias is defining and identifying it, a thorny issue the report’s authors tackled:

Obviously, only a tiny percentage of law enforcement officials are likely to be active members of white supremacist groups. But one doesn’t need access to secretive intelligence gathered in FBI terrorism investigations to find evidence of overt and explicit racism within law enforcement. Since 2000, law enforcement officials with alleged connections to white supremacist groups or far-right militant activities have been exposed in Alabama, California, Connecticut, Florida, Illinois, Louisiana, Michigan, Nebraska, Oklahoma, Oregon, Texas, Virginia, Washington, West Virginia, and elsewhere. Research organizations have uncovered hundreds of federal, state, and local law enforcement officials participating in racist, nativist, and sexist social media activity, which demonstrates that overt bias is far too common. These officers’ racist activities are often known within their departments, but only result in disciplinary action or termination if they trigger public scandals.

As the report notes, the federal Justice Department has “no national strategy designed to identify white supremacist police officers or to protect the safety and civil rights of the communities they patrol,” though there are signs that the Biden administration will take the issue more seriously than President Trump ever did: in his confirmation hearing, Attorney General nominee Merrick Garland—who prosecuted the case against Timothy McVeigh, the Oklahoma City bomber—said that pursuing white supremacists would be central to his department’s work, including filing charges against participants in the January 6 riot at the Capitol, which included dozens of off-duty police officers.

But there have been other attempts to quantify the “racist, nativist, and sexist social media activity” of law enforcement officers. In a 2019 paper titled “KKK in the PD: White Supremacist Police and What to Do About It,” Georgetown law professor Vida B. Johnson identified more than 100 police departments in 49 states that have faced public scandals over racist texts, emails, or social media posts by officers since 2009. Also in 2019, the Plain View Project published a report compiling more than 5,000 bigoted social media posts by some 3,500 accounts identified as belonging to current and former law enforcement officials in just eight jurisdictions. Locally, groups like Hate Watch Report (focused on the Upper Hudson Valley and Taconic Hills), Green Book Hudson Valley, and the Hudson Valley Antifascist Network are monitoring and exposing hate groups and other extremists in the region; their revelations have sometimes identified local law enforcement as participating in extremist behavior.

Many officers, when confronted about offensive social media activity, have defended their actions, if not the content itself, on the basis of free speech. But as William Finnegan writes for The New Yorker, “police officers do not enjoy the same expansive First Amendment freedoms that civilians do, at least not if they want to keep their jobs,” a precedent established in case law at least as early as 1892, when the Massachusetts Supreme Court upheld the firing of a cop for violating a local law prohibiting officers from soliciting political aid or donations. The officer “may have a constitutional right to talk politics,” future US Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. wrote, “but he has no constitutional right to be a policeman.” The Brennan report similarly notes that “most courts have upheld dismissals of police officers who have affiliated with racist or militant groups, following Supreme Court decisions limiting free speech rights for public employees to matters of public concern.”

Johnson, the Georgetown Law scholar, put it more succinctly in an interview last month with the Los Angeles Times: “People who can’t separate fact from fiction probably shouldn’t be the ones enforcing laws with guns.”

If you have knowledge of offensive online activity by local law enforcement, you can email [email protected] or contact editor Phillip Pantuso on Signal at (817) 832-4547.