Update: On Thursday, June 9, the Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) announced that the Delaware Aqueduct shutdown will be delayed until next year. It now projects the shutdown will begin on October 1, 2023 and end May 31, 2024.

The delay is due to a few preparatory projects that still need some work, according to DEP spokesperson Edward Timbers. These include: connecting the Croton Filtration Plant to City Water Tunnel #2; a project to facilitate moving water around at the Cross River and Croton Falls pumping stations; and projects to secure backup supplies of water for affected upstate municipalities.

"Because there are so many projects, there was never a set date for a shutdown," says Timbers. "Rather there is a window of time within which planners determined all the necessary projects, hydrology etc. would align to allow for a successful shutdown. Today we are announcing that we expect the shutdown to happen in the fall of 2023."

Do you know where your water comes from?

Sometimes it’s obvious. If you live in a rural house that has its own well, you probably have a pretty good idea. Sometimes it says on the bottle: an aquifer in Fiji, springs at the foot of the French Alps or the little town of Poland, Maine.

Sometimes it’s not that obvious. Turn on a tap, and you might get water that's traveled from dozens or even hundreds of miles away.

This fall, New York City will embark on a hugely ambitious engineering project that could impact people throughout its water supply system, from rural people in the Catskill mountains to New Yorkers in the five boroughs who rely on upstate water every time they turn on a tap. If all goes smoothly, few might even know the project is happening. But if the city’s water plans go awry, people throughout the state could get a rough education in where water comes from, and why it matters.

Turn on any tap in New York City, and about half of the water that comes out has traveled there all the way from the headwaters of the Delaware River, more than 100 miles upstate.

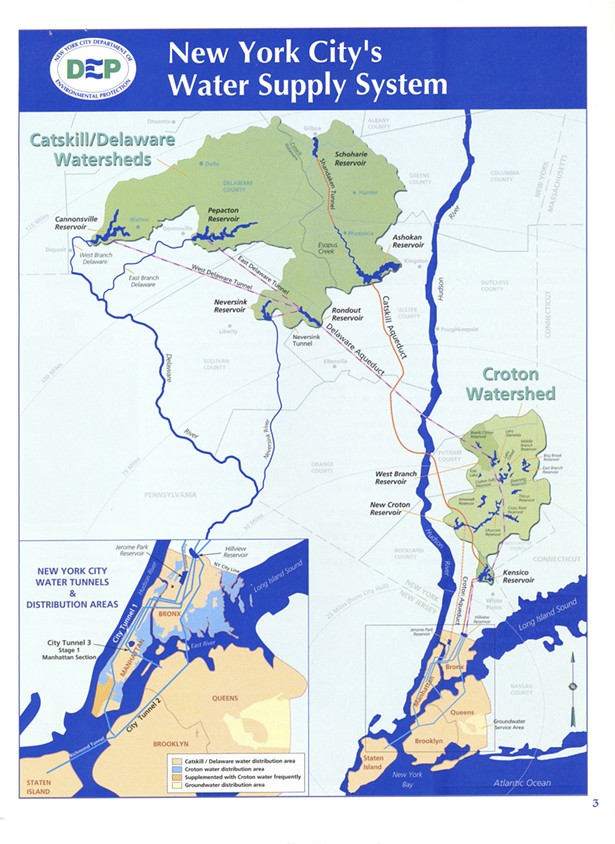

New York City gets its water from a far-reaching water supply system governed by the city's Department of Environmental Protection (DEP). The DEP bears the mandate of providing water to 8.5 million city residents and another 1 million residents in the surrounding counties of Westchester, Putnam, Orange, and Ulster.

Together, New York City and its water-supply neighbors consume about a billion gallons of drinking water a day. To supply 9.5 million people with that much water requires a 2,000-square-mile watershed, with countless miles of pipes and infrastructure that reach out to reservoirs of the Hudson Valley and the Catskill Mountains and bring water back into the city.

About half of the one-billion-gallon daily supply comes from four reservoirs on the upper Delaware River: the Cannonsville, the Neversink, the Pepacton and the Rondout. Together, those reservoirs provide the city with around five to six hundred million gallons a day, depending on the day and the conditions of the system.

All that water flows through a single underground tunnel: the Delaware Aqueduct. And this fall, the DEP is going to temporarily shut that aqueduct down.

The Delaware Aqueduct was originally built in the 1930s and 40s. It connects the Rondout Reservoir in the southern Catskill mountains with the West Branch Reservoir over in Putnam County. From there, the Aqueduct passes through several reservoirs in the Hudson Valley before depositing its water into the Hillview Reservoir on the outskirts of the Bronx. At 85 miles long, it holds the title of the longest tunnel in the world, and has been dubbed “the eighth wonder of the world” as a marvel of 20th-century engineering.

It's a critical piece of infrastructure to New York City. But it's also a damaged piece of infrastructure, and has been for decades.

The DEP began monitoring two leaks in the aqueduct early in the 1990s, one in the Orange County hamlet of Roseton near Newburgh, and one in the Ulster County town of Wawarsing. The two leaks combined release around 20 million gallons of water per day, with 95 percent of that total coming from the Roseton leak.

Plans for the repair of the aqueduct have been taking shape for years, and are now in place. The DEP has built a 2.5-mile bypass tunnel under the Hudson River, which it plans to connect to the main tunnel before and after the leaking section of the aqueduct under Newburgh, and it plans to grout closed the leaks in Wawarsing. It's a billion-dollar project, and it's one the DEP has been planning for decades.

To accomplish these repairs, the DEP needs to shut the aqueduct down and drain it, allowing work to be done on the inside. Repairs are scheduled to start in October, with a projected shutdown of five to eight months.

Keeping a Close Eye on the Watershed

It's easy to see the impact this might have on New York City. A community losing access to half its drinking water, even temporarily, is a big deal, especially when it’s a community of 9.5 million.

But the city’s water system planners aren’t worried that New York will run out of water while the aqueduct is shut down, in part because they have planned ahead to have some flexibility to delay the project if the conditions aren’t right to carry it out.

“We'll want to have ideal conditions in order to make the shutdown and connect the bypass tunnel,” says DEP director of communications Edward Timbers. “If it happens that we don't have ideal conditions, we will wait until the following fall/winter season.”

The basic plan for ensuring that New York City has enough water during the shutdown involves using the Catskill Aqueduct, the city’s other main water conduit, to balance use between the Delaware reservoirs and others in the Catskills and the Hudson Valley.

The DEP plans to take more water than usual from the Delaware reservoirs prior to the shutdown, drawing down those reservoirs to around 30 percent of their normal capacity and letting the reservoirs elsewhere in the watershed fill up. Once the Delaware Aqueduct shuts down, the DEP will switch to drawing water from the Catskills and Hudson Valley reservoirs through the Catskill Aqueduct, relying on the water that filled them up while it was emptying the Delaware reservoirs.

One change New York City residents might notice while the repair project is ongoing: Their famously delicious water will taste different. Naturally occurring soil compounds called geosmin and methylisoborneol, harmless compounds whose levels rise in the fall throughout the city’s reservoir system, cause water to have a musty or earthy smell. In a normal year, the DEP would manage their impact on the water supply by switching between reservoirs when concentrations rise in one part of the system, but with the Delaware Aqueduct shut down, there will be several months with little flexibility in the system for switching.

When the aqueduct repairs are finished, the DEP will open the floodgates and use mostly water from the Delaware reservoirs until levels in both water supply systems are stable.

The Delaware Aqueduct repairs are part of a larger set of repair projects across the city’s water supply system, collectively known as the Water for the Future project, some of which needed to be completed before the shutdown to prepare for the aqueduct going offline. Foremost among these projects was the rehabilitation and repair of the Catskill Aqueduct.

Over the course of its lifespan, the Catskill Aqueduct gradually lost some of its capacity due to a buildup of biofilm on its interior, a phenomenon that formed quickly in the years after the aqueduct first came online in 1915. The accumulation on the tunnel’s walls reduced the Catskill Aqueduct’s capacity from 660 million gallons a day down to roughly 590. The repair project, conducted between 2017 and 2021, restored the aqueduct to its full capacity, helping to facilitate the DEP's balancing act between the Delaware and the Catskill reservoirs around the shutdown.

While the Catskill Aqueduct project gave a boost to water supply, other Water for the Future projects took aim at reducing consumption in the city. Between 2013 and 2018, the DEP spent $50 million on upgrades to improve water conservation, retrofitting older equipment with more efficient models, funding water recycling systems and increasing public awareness around water consumption. Those upgrades helped to bring the city's average demand down from more than 1 billion gallons a day in 2012 to 979 million gallons a day in 2021.

The DEP is relying on forecasting as well as planning to ensure the shutdown goes smoothly.

In a meeting on April 7, DEP Bureau of Water Supply Chief of Staff Jennifer Garigliano, who plays a key role in the Delaware Aqueduct repair planning, spoke to the Upper Delaware Council, an organization that manages the upper Delaware River in partnership with the National Park Service, about those plans.

The DEP has a great many resources invested in forecasting conditions in the watershed, said Garigliano. “We're going to watch it very closely…leading into the shutdown, during the shutdown, and even after the shutdown.” If the conditions don't look good, the city won’t shut down the aqueduct. One of the city’s most important tools for forecasting watershed conditions is the Operations Support Tool, an $8.5 million computer modeling system launched in 2014 that draws on weather forecasts, snowpack and stream data as well as operational data from the reservoirs, and can model the impact of different alternate future scenarios and planning decisions.

As a last resort, the DEP can bring the Delaware Aqueduct back online even in the middle of repairs, according to the Water for the Future Program's environmental impact statement. “If, at any given time, system demand exceeds predicted available supply, demobilization from the RWBT [the Roundout/West Branch Tunnel, the portion of the Delaware Aqueduct that runs under the Hudson River] bypass tunnel connection would be initiated, the RWBT would be brought back into service and the water supply systems would be allowed to return to typical conditions.”

The region has seen more wet years than dry over the past decade. The Delaware River Basin, which includes New York City's watershed and spans four states, experienced a series of emergency flood events between 2004 and 2006 that brought the river to its highest point since 1955, when record flooding killed 99 people throughout the basin. The basin experienced further flooding in 2003, 2011, 2020 and 2021. Flooding from Hurricane Irene in 2011 caused devastation and death across the East Coast, and was particularly intense in the Catskills region where New York City’s watershed lies.

That trend seems likely to continue. A summary of the 2021 weather for the upper Delaware region released by the National Park Service indicated that it was the fifth warmest and the twenty-third wettest year on record. Precipitation has increased almost half an inch every decade since 1895.

Already in 2022, floods have struck in the upper Delaware. Heavy rainfall on April 7 and 8 led to moderate flooding along the East Branch of the river, and minor flooding along the river's West Branch. The Neversink, Pepacton and Cannonsville reservoirs all spilled over, with reservoirs all filled over 100 percent and excess water spilling out over the top of the reservoir's dams.

“The issue of climate change is just so important here,” says Skelding. With the region seeing increasingly dangerous storms, he believes the DEP needs to pay close attention to local flooding concerns during the shutdown.

The DEP has told upstate watershed communities that the agency will weigh conditions throughout the watershed as it decides whether to go ahead with the shutdown or not. The DEP has the option to bail out and push the shutdown back a year if conditions are too dry, for fears of water shortages in the city, but it can also exercise that option if conditions in the watershed are wet enough that flooding is a concern.

If everything works out, the upper Delaware region should weather the situation without major flooding events. But the possibility of flooding is there, and it's one local residents—and businesses—are keeping an eye on.

“Flooding is inevitably an issue with any business that's near or on the river,” says Evan Padua.

Evan and his father Mike Padua run Sweetwater Guide Service, which offers guided fishing and floating boat tours along the upper Delaware River.

The large water releases the DEP will use to help draw down the reservoirs in preparation for the shutdown aren't necessarily a huge flood risk, Padua says. He's more worried about the possibility of flooding the following spring: If the repairs to the aqueduct take longer than expected, the reservoirs could fill up with rain even at maximum releases, and the DEP won't have a way to control flooding from the excess water that spills out over the top of the dams.

Padua is fairly sanguine about the possibility of flooding. There will always be a risk of floods, he says, with or without repairs. The fishing boats and guide services along the river can generally find water to work in, consolidating in areas of the river that have received less rain.

While those who depend on the river for their livelihoods can adapt to changes in flow, infrastructure like roads, bridges, and buildings downstream of the reservoirs is vulnerable to increasingly severe weather. The accelerating pace of climate change means that the flood risks associated with taking the Delaware Aqueduct offline will only increase with every passing year, if the repairs are delayed.

Getting the Word Out

Skelding is hoping for the best, but he says many people in the upper Delaware aren’t aware that the shutdown is coming. He's advocating for robust public outreach from the DEP.

In recent months, the DEP has embarked on a campaign to spread the word in the upstate watershed.

Garigliano has made the rounds of regional conservation councils, presenting on the shutdown and on the DEP's plans for its management. She presented to the interstate Delaware River Basin Commission on March 23, and the Upper Delaware Council, a partnership of local, state, and federal governments and agencies, on April 7.

At the April meeting, members of the Upper Delaware Council asked Garigliano how that communication would persist going forward. What happens if flows deviate from the plan? How will the DEP let people know?

The DEP is still building those avenues of communication, said Garigliano. So far, DEP representatives had gotten the word out mostly through attending different conferences and meetings. The DEP also has an emergency plan to mass-send recorded messages to people's phones, social media pages, and the like. In the event of a major flood, the DEP can work with the National Weather Service to issue alerts.

“There are many avenues, in the event that something goes wrong, for us to get a message out, or if we're starting to see something,” said Garigliano.

Life Above the Leaks

The impacts at either end of the Delaware Aqueduct will only hit as the aqueduct gets shut down. Those in the middle are already decades in the making.

The water leaking from the Delaware Aqueduct in Wawarsing and Roseton didn't vanish into the ether after it left the aqueduct. It bled out and into the groundwater of each town, affecting residents and local wells.

A 2017 environmental impact statement released for the Water for the Future program indicated 145 parcels with current or potential wells in Wawarsing that the leaking aqueduct could impact, and 27 in Roseton.

Residents in Wawarsing felt those impacts firsthand, experiencing flooded wells and homes. According to a study done by the US Geological Survey, these issues were first reported by Wawarsing residents in 1992.

Laura Smith was affected more recently. She and her husband bought a house in Wawarsing in 2003. They noticed a little water in their basement the following year, she says. But their first encounter with major flooding took place in the first few weeks of April, 2005.

Flooding in their home became a constant presence in the time she lived there, Smith recalls. “We flooded in the wintertime; we flooded at every season in the year.” Smith and her neighbors were pumping water out of their basements for weeks at a time. “We were all flood mitigators,” she says.

The residents of that neighborhood had an early inkling that their flooding issues were related to the leaking Delaware Aqueduct; Smith recalls older residents telling her about the aqueduct when she first asked around about the flooding in the area. But the early conversations she and other residents had with the DEP were difficult, and it took a significant amount of local organizing and reaching out to local representatives to have the DEP hear their concerns.

The DEP asked the US Geological Survey to study the area in 2008, prompted by local reports of flooding. Four years of study later, the USGS determined in a pair of studies that, while higher-than-normal rates of precipitation was a major contributor to flooding regionally, leakage from the Delaware Aqueduct had a measurable contribution to local issues.

Under increasing pressure to address the problems of homeowners in the area of the leaks, the DEP had a number of responses to the concerns of Wawarsing residents. “DEP partnered with the Town [of Wawarsing], and Ulster County and has provided more than $25 million dollars for local programs to address water concerns,” says Timbers; those programs included pumps, testing and water treatment systems.

As the USGS studies completed, the DEP turned to another form of resolution: paying residents to leave the area. “A home buyout program… [helped] 39 residents relocate and return those areas to green space,” says Timbers. “A neighborhood repair program improved drainage, waterproofed basements and added gutters to 38 other residents that desired to stay in their homes.”

Smith was one resident who took the buyout. Her home and those of her neighbors were demolished and removed, leaving the area as open space.

Smith says it was the organization and the action of local advocates that forced the DEP to respond. “We knew, if we didn't do anything, we were sinking.”

Moving a billion gallons of water a day into New York City is no easy task. Doing so with aging infrastructure in a changing climate is doubly so.

As complex as it is, most of the time the system just works. You can turn on a tap and have water without needing to know where it came from. It's when the system breaks down that knowledge and advocacy become important. Smith learned a lot about the geology of her area when she had to look into the flooding in her basement, she says.

If the shutdown of the Delaware Aqueduct goes as planned, disruptions to the watershed should be minimal, and New York City will have plenty of water. By 2023, the aqueduct's reopening should restore the system to its normal functioning.

But whether or not the repairs proceed without a hitch, Skelding is urging the city to be open and transparent with residents throughout its water system. “Everybody has a stake in this.”