Throughout New York State and the Hudson Valley, people who swore an oath to serve the sick are working at tremendous risk to themselves and their loved ones, struggling against hostile conditions to save the lives of people stricken with the novel coronavirus. They face long shifts, staff shortages, reduced supplies of personal protective equipment (PPE), inadequate support from state and federal governments, and—if they discuss any of it publicly—the loss of their livelihood.

They are confused, frightened, and furious.

Some of them have even lost their lives in the performance of their duties. As of May 1, 22 nurses and hospital workers had died from COVID-19 in New York State, according to the New York State Nurses Association (NYSNA). In Washington, DC, nurses with National Nurses United gathered in front of the White House to read the names of 45 colleagues who died while treating COVID patients. Others have been disciplined or fired for speaking out. Doctors, nursing assistants, technicians, janitors, cooks, and other hospital staff are similarly vulnerable.

In response to these circumstances, NYSNA, the state’s largest union for professional nurses, filed three lawsuits against the New York State Department of Health for failing to ensure safe working conditions, adequate protective gear, and proper training for redeployed nurses. In Kingston, NYSNA sponsored a Rally for Safe Hospital Care across the street from HealthAlliance Hospital.

Out of fear of their administrations, local nurses were reluctant to discuss their experiences with The River. Some, however, were willing or motivated to do so on the condition that they remain anonymous. Below are statements from three of them, edited for clarity and length.

***

A registered nurse in the intensive-care unit at an undisclosed hospital in Westchester County:

Working in the intensive-care unit is like pushing your way through a busy New York street. We started preparing for this in February. I care for six patients during a 12-hour shift, working in a mask that I can’t really breathe in. I work exclusively with COVID patients right now. In March, we canceled elective surgeries and started taking overflow patients from the New York metro area. We reorganized our floors and added additional units. Exposure is a big concern. I’m sure I’ve been exposed multiple times.

Yesterday I felt like I was going to pass out. Something wasn’t right with the mask. You’re breathing your own carbon dioxide and you get dizzy and tired. I get headaches. We’re dehydrated, too. We can’t drink or eat anything until we get a break, which doesn’t always happen. Yesterday I took a 20-minute break and a 10-minute break over a 12-hour shift. The gear isn’t heavy, thank God.

Getting this virus is awful. I’m taking care of a young, middle-aged man who has underlying medical conditions but was otherwise healthy and working. For the first few days, he was symptomatic but okay. Then suddenly he went downhill. We took him in intensive care and put him on a ventilator to keep him alive. He was terrified. It was the last time he saw his family. That was three weeks ago.

To prevent the virus from spreading, the hospital doesn’t allow COVID-positive patients to see anyone, including family, so this man is alone. I think that’s the worst part of it for me, seeing these people struggle in isolation. We’re their only source of human contact, and we’re covered from head-to-toe in protective gear.

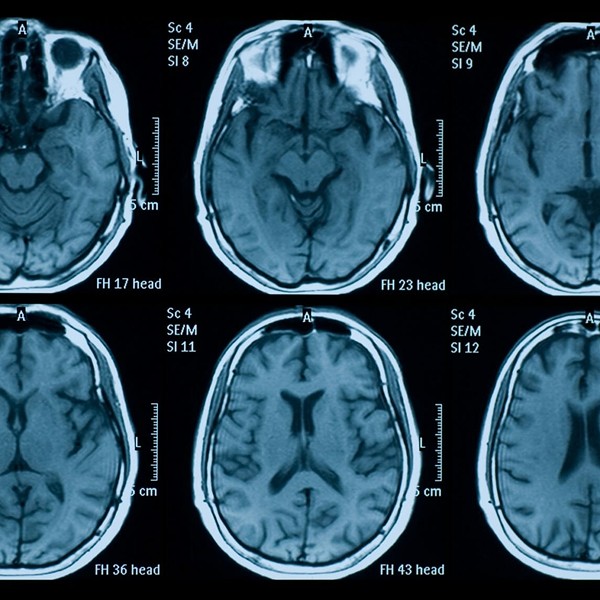

We don’t think he will make it. The ventilator is breathing for him, but it can’t deliver oxygen everywhere in his body. If you’re ventilated long enough, it takes a really big toll. It differs between patients, but without oxygen, the brain and other organs suffer damage and eventually fail. You’re given paralyzing agents and medications that induce a coma, so this man doesn’t know what’s going on, and we don’t know what’s going on in his mind. He’s barely alive. He must be so sad and scared.

I don’t want to take him off the ventilator. There’s always the thought of, “Well, what if he gets better? Why don’t we give him another week?” But from what we can see it’s not good at all. His family hasn’t come to a decision. If they decide to let him go, they’ll be allowed to see him one last time to say goodbye. We’ll give him morphine, take him off the ventilator and ease him into his death.

As much as you try to remove yourself from a crisis like this, it takes an emotional toll. It’s just a lot of death and people on the brink of death. Before COVID, our patients improved. In the ICU, we lose maybe three out of six patients. But there are positive stories. I got to send two patients back to the medical floor the other day. That was the first time I saw people get better.

The changes in the rules are another part of this. The hospital emails them to us every night. They’re driven by speed and scarcity, but some of them seem obviously dangerous. Our patient documentation is minimal now and we don’t change protective equipment between COVID patients. But they also changed the amount of time that we can leave in intravenous tubing that goes directly to a patient’s heart. We used to change it every 24 hours to prevent infection. Now we can leave it in for four days. How is that safe?

It’s just sad. A worst-case scenario really. I probably won’t process it until summertime, because it’s too much.

A registered nurse at an undisclosed hospital in the Hudson Valley:

My heart dropped the first time I saw my name written on the board for a COVID assignment. I felt heavy and sick. I have asthma, and you hear these devastating stories about healthy hospital workers getting ill and dying. “This is it,” I told myself. “You can’t turn back now. You have to do what you came to do.” I started tearing up. Thankfully I had a second nurse to help me.

You can tell that everyone’s scared. No one really knows what they’re doing. All the changes are frustrating because one day you’re doing something right and the next day it’s wrong. We’re not sure what to believe about what’s effective against the virus and I’m afraid of hurting someone. It’s scary how little we know about it. I feel like it picks and chooses people for reasons we don’t understand. Can you get it if you’ve already had it? Can you spread it if you’re negative? How can you be sure you’re not going to get it?

It’s really hard to see patients with COVID. They’re powerless. Their lives are in our hands and the care we give. We kind of have to put on a show of positivity, because if they see how scared we are, it will be worse for them. It’s especially hard with patients who are aggressive or mentally ill. At the end of the day we do our best.

My colleagues and I talk in the break room at lunch. We share food and tell jokes, and it brightens our spirits. We talk about not getting hazard pay and how hard it is to keep a distance from our families at home. It’s hard to see people online complain about having to stay home because of the pandemic. I think I would cherish the chance to spend more time with my partner. I don’t think I’d be able to do what I’m doing if I were alone right now.

Several of my colleagues are upset because we were supposed to vote to form a union and the vote was delayed because of the pandemic. I haven’t been a nurse long enough to know if the union would help me or not, so I don’t feel strongly about it. Our management obviously doesn’t want it. I imagine they’re doing the best they can under the circumstances. If I have a concern, I’ll voice it and hopefully I won’t get reprimanded. I just try to do my work, stay out of everyone’s way, and come home. It does suck to have to be so cautious about what I can talk about. We hear about nurses getting fired for criticizing their hospital. That’s terrifying and inappropriate.

Some nurses say they wouldn’t have entered the profession if they knew what we’d be going through today. I became a nurse because I was interested in the human body, how involuntarily it works. I took an anatomy class in high school and then a relative of mine became a nurse and it seemed promising. You can always get a job and the pay is okay. Sometimes I think about changing my career, but I don’t think I would. What’s happening now will go down in history. I remember sitting in class and hearing my professors talk about what it was like during the AIDS epidemic, how frightened they were, how little they knew, and what they did to protect themselves and others. They were so brave and devoted to their profession. It’s inspiring to be doing that now, making history. I’ll be able to tell people about it.

A registered nurse in the labor and delivery unit at an undisclosed hospital in Rockland County:

There is a misconception that labor and delivery staff don’t deal with the virus as much as other units do. In labor, patients breathe all over us. Despite Governor Cuomo’s order for nurses to get one N95 mask per day, I get just one mask per week. I keep it in a paper bag. We reuse gowns and face shields, wiping them down with sanitary wipes and hanging them up. It’s not what we were taught in nursing school.

I know a lot of nurses who can’t sleep. We hear alarm bells going off all night. Our anesthetists are taxed with COVID patients, so women in labor have to wait to get relief from pain. Doctors run in and out of our unit and I see in their faces that they’re exhausted because some of them now double as critical-care doctors. When I walk into work in the morning, I pass refrigerated trailers that are set up as morgues. One night my hospital had 11 deaths. Our security guard helped carry them out. Some mornings I sit in my car and cry.

Normally there are lots of family members and birthing coaches around our unit. It’s supposed to be a happy, joyous time, but since the pandemic hit our hallways have been empty. At first we didn’t allow family, friends, or spouses to be present during birth. I had to FaceTime a father while his wife delivered their child and it was difficult because she was distressed and we’re working with a diminished staff. Now we allow one companion to be present per mother. We question them and check their temperature and make them wear a mask.

We don’t yet know how this virus can affect newborns. Typically, when a baby is born, we place them against their mother’s skin. This is a significant bonding moment. But if the mother has the virus or is suspected of having it, we take the baby immediately to minimize exposure. The mothers cry. It’s sad and these decisions are hard, but we support them to protect everyone.

For a variety of reasons, our patients are not always honest with us. One woman claimed she didn’t have the virus and when the delivery was over she told us she was positive. That means she exposed her baby—who was put to her skin—and the whole staff to COVID. We have two separate nurseries now, one for babies who may have been exposed and another for those who are being monitored.

The other day I went into a delivery without a face shield. We didn’t have one, but I wasn’t going to abandon the mother. When we finished, we went looking and found just two shields for an entire unit. My husband and I talked about what I should do in moments like this. Some people say there’s no emergency that’s worth running into a room without proper equipment, but I swore an oath to care for people. That mother and baby needed me. You can argue that if you get sick, you can’t do your job. But I’m not going to say, “I’m sorry, I can’t help you.”

We shouldn’t have to decide whether we will care for patients because we lack proper equipment. Some nurses walked out and lost their jobs. I understand their decision. A nurse in her thirties at a hospital not far from mine died from COVID. Two others were life-flighted to Albany Medical Center. Some working nurses are pregnant, and several of our staff tested positive. Our managers tell us, “If you don’t have a fever, then come to work,” but you can have the virus and infect others without having symptoms, so people are coming to work sick. People say, “You signed up for this,” but we didn’t sign up to risk our lives. My kids didn’t sign up for it. My husband didn’t sign up for it. We’re sacrificing a lot for our families, their health included.

If you do get sick, you’re required to fill out a form that asks if you wore the proper PPE. It feels like a trick question. If you answer honestly and say “No,” then presumably you’re liable for the consequences. So we’re told to follow a protocol that jeopardizes our jobs and livelihoods in addition to our health. It’s not fair to expose nurses that way. We discuss this sort of thing in private groups on Facebook, because if the hospital sees us saying anything in public we can be fired.

It is shocking that we have these problems in the United States. We really, really depend on the community right now. One woman donated a bunch of homemade face shields, and I’ve seen doctors wear ski goggles and bandanas over their mouths. Who let this happen? Why are we fighting and buying our own equipment? We’re disappointed in our hospital and the union, and we’re hearing it all over. We feel as if no one is protecting us.

As a profession, we are appalled. We never should have been put in this position. We’re going to have a lot of mental-health issues after this. The people you trust and depend on are going to be broken. We fear young people won’t choose this profession. We feel very strongly about our oath, but we’ve been betrayed. We need to be able to trust our hospitals, our unions, and our government. When this is over, nurses are going to fight. We’re warriors when we come together. We’re not going to let this happen again.