Danielle Cannon starts every day with the same ritual: Wake up; make breakfast for her 11-year-old son, Pharaoh; feed her birds; and brew herself a decent cup of coffee. Keeping a consistent schedule at home is the only thing anyone really has control of these days, and Cannon tries to make the most of it. She’s the type of person who doesn’t merely hope for the best—she was raised to prepare for the worst, and she has been in tight spots before the coronavirus upended daily life. A Hyde Park resident employed as a paraeducator, one-on-one teacher aide, and bus monitor, Cannon couldn’t take her work home when New York implemented its statewide lockdown. Financially, she feels that she will be able to ride out the summer, but her biggest concern isn’t paying the mortgage on time—it’s the wellbeing of Pharaoh, who has nonverbal autism.

With schools across the country closed due to the coronavirus pandemic, remote learning has become a new challenge for many families. For parents who have children with developmental disabilities, there is the added fear that their kids won’t just lose out on their current education, but that the educational and social skills they’ve built up over the years will erode. Families have reported signs of regression since school doors closed and parents may continue to bear the weight of their children’s education through the summer.

“I’m doing six times the job that they would do in school,” says Cannon. Pharaoh is one of the more than 460,000 disabled students in New York. Normally he would receive additional services, such as speech, occupational therapy (OT), and physical therapy (PT) through his Individual Education Plan, to help him interact in society. IEPs aren’t simple privileges bestowed to students—they’re a right protected by state and federal law.

“It is essentially the contract between the school district and the family that lays out all the support and services a student with a disability requires to make progress in school,” says Maggie Moroff, special education policy coordinator at Advocates for Children of New York. Moroff also helps coordinate the ARISE Coalition, a collection of parents, advocates, academics, educators, and other stakeholders who push for systemic changes to improve day-to-day experiences and long-term outcomes for students with disabilities in New York City public schools.

IEPs serve as blueprints for the services provided to students, dictating how often they receive additional sessions and what their optimal classroom setup looks like. “If a service is on the IEP, the Department of Education is required, by law, to then provide that service,” Moroff says.

The law regarding IEPs was written in 1975 when Congress recognized the need for a federal law to help ensure that local schools would serve the educational needs of students with disabilities. The original law was titled the Education for All Handicapped Children Act. That first special-education law has undergone some name changes with additional amendments, but today we know the law as the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, or IDEA. It gives states federal funds to help make special-education services available for students with disabilities, and also provides very specific requirements to ensure appropriate public education is provided to families and children who qualify for the assistance. But the law wasn’t written with social distancing in mind.

Ideally, and legally, programs and services such as OT, PT, and speech would be administered by trained and certified professionals, and students would encounter these programs in hands-on sessions. But given the stipulations in place to prevent the spread of COVID-19, parents of children with special needs are now finding themselves as untrained substitutes, with assigned therapists giving guidance over video platforms or via written instruction.

Addressing Problems, Seeking Solutions

“Schools should not be 100 percent remote. Period,” Dutchess County Executive Marc Molinaro said during a virtual town hall on May 22. Based on New York’s guidelines for reopening, education facilities are able to resume in-person instruction during Phase Four. Thanks to pressure from New Yorkers—including Molinaro, who has sent letters to Governor Andrew Cuomo’s office in hopes of addressing the struggles families with special needs are facing—the governor signed an executive order on June 5 that gives schools the option to provide in-person special-education services over the summer. But parents and programs report that the state department of education has provided little to no guidance on how to open up campus services.

“I don’t think that the state should get a free pass on this,” Molinaro says. “They established guidances for tennis and guidances for beaches and guidances for retail space. Why guidance for those with developmental disabilities wasn't a priority speaks volumes about the way the state of New York treats those with developmental disabilities—not the staff people with [the New York State Office for People With Developmental Disabilities], not the workers who are out there trying to do their job, but from a leadership perspective. Those with developmental disabilities have often felt that they were treated as second-class citizens, and when you consider the fact that here we are in the midst of all of this, establishing those guidelines and those protocols ought to have been a priority, not a secondary thought.”

Molinaro urges schools in the county to think very carefully about whether or not they should provide services, regardless of what plans were put in place prior to the executive order. “Every 24 hours there is a new dynamic that we are being asked to construct, and I think that in this case, again, nothing is cemented,” he says, adding that while the state hasn’t provided guidance thus far, other established protocols can be used. “It was decided, and it can be decided differently.” Molinaro understands the necessary intervention techniques that only therapists can provide, as his daughter, Abigail, has autism.

“In some cases, using the virtual connection, using technology, can be a great experience for some young people with disabilities, because it's a tool and a practical lesson. But so many others need to have that direct connection with their speech therapist, their occupational therapist, their physical therapist. There needs to be that direct connection at times to assist those who struggle the hardest,” says Molinaro. “There are families who struggle very hard to provide care for their child, for a family member with a disability, and those therapists, those teachers, those providers are perhaps the one and only professional who can make that absolute connection.”

Making the Best of the Situation

Cathy Collyer, a registered occupational therapist based in Westchester County, is seeing some of these struggles first hand. “What makes it really hard for parents is they’re being pulled in a lot of different directions,” she says. Collyer has been in the field for 35 years, and since the start of the stay-at-home orders, she has offered her early intervention services via telehealth to her clients. As a practitioner, she knows that the delivery system isn’t ideal for everyone.

“The population that is struggling the most are the kids on the autistic spectrum and their parents,” says Collyer. “Those kids are a real handful to work with over screen.”

Many parents of children who are on the spectrum have reported issues getting their children to engage in learning activities online. Methods to mitigate the behavioral issues presented by autism are best served through applied behavioral analysis, better known as ABA therapy. This type of therapy entails rigorous, one-on-one, hand-over-hand intervention that breaks down desirable behaviors in a way that allows those on the spectrum not only to perform the prompted lessons but to retain those skills throughout their lives. “This is a very difficult mode of treatment delivery for them, even if I can educate a parent and explain different strategies and techniques,” says Collyer, noting that some parents are easier to guide than others, but teaching how to administer OT from a distance can be a struggle. “It’s very hard to teach a parent how to do skilled handling techniques. I don’t know that I could guide a graduate student in a technique that they’re unfamiliar with,” she says. “So trying to teach a lawyer, or an administrative assistant how to do skilled handling? There are just some things we can’t do.”

Cannon is aware that she may not be the best person to provide the therapy methods Pharaoh needs. “We are not capable, we are not trained, we are not certified to teach them what they need to know,” she says. But given her work experience and the fact that she works at the very same school in which her son is enrolled, Cannon has some additional insight into how to handle Pharaoh’s education.

“I have previous experience with special needs, not just my own [son’s], so for me to come home and have to be the teacher, I have a background to try to fall back on,” she says. “I can’t even imagine what it’s like for the parents that don’t work in the school.”

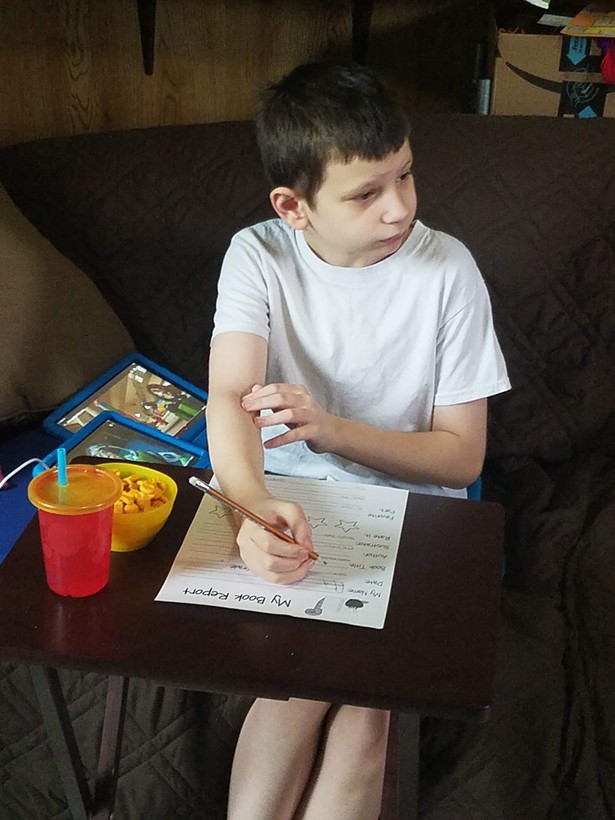

Beth Poague, who works full-time from home and has no such experience, says, “If we come out of this potty-trained, I’ll consider it a success.” Initially overwhelmed by the transition, Poague is gradually getting used to the classrooms being online. Her youngest son, Finnegan, 6, has a rare genetic mutation called PACS1 syndrome, a condition that presents a myriad of disorders, including underdeveloped muscle tone, delays in language and speech, and intellectual and neurological conditions that are akin to autism, which can make learning in conventional classroom settings difficult. As a result, Finnegan experiences delays in speech and mobility, and has sensory processing issues, along with an intellectual disability.

When school was in session, Finnegan was in an environment with the lowest student-to-teacher ratio in the Beacon City School District, 6-to-1, in a self-contained classroom to address and manage his needs in the least restrictive environment possible. Within this setting, Finn received speech, OT, PT, and engagement in social-skills groups. Socialization is vital for children on the spectrum or who have similar processing disorders. But with social-distancing orders in place, creating an environment for these children to learn how to interact with society, or just those outside of their family circle, is nearly impossible.

“Before this all started, we got Finn placed for an hour and 45 minutes in a general-education classroom,” says Poague, who is disappointed that her son won’t be able to engage in peer interaction beyond a computer screen. However, she is trying to capitalize on what is within their limited control and the requirements of Finnegan’s IEP. With the assistance of her son’s teachers and therapists, Poague has set specific goals to strive for, and together they are figuring out what is working and what isn’t.

“What we are doing is choosing what to focus on,” Poague says. “Basically, if we get out of this pandemic and he can run, swinging his arms, and he doesn't regress in his speech, then we have done an okay job.”

While Poague is setting more limited goals, she can’t say for sure if Finnegan has regressed at this point. At minimum, many parents of students with disabilities suspect their kids aren’t progressing in their development with schools shut down. But it’s also difficult to gauge what may have been lost, as parents may not have the full picture of where their children were prior to the closures.

“As parents, we’re not taught these things, the therapies. We’re not allowed to,” says Cannon. Prior to her gaining employment at the Salt Point BOCES, Cannon had done two internships at the school while Pharaoh was enrolled in its special-education program. “I couldn’t sit in on therapy because of confidentiality and the other students who were there with him,” she says. Cannon hopes that when schools reopen, there will be a better contingency plan in place. For the time being, parents can only work with what knowledge they have and what resources are available.

Thriving Outside the Classroom

For the families that have students who require more traditional educational approaches, each passing day out of the classroom raises concerns for their child’s future. But while this learning format isn’t ideal for most, there are some people who are able to thrive in this new environment.

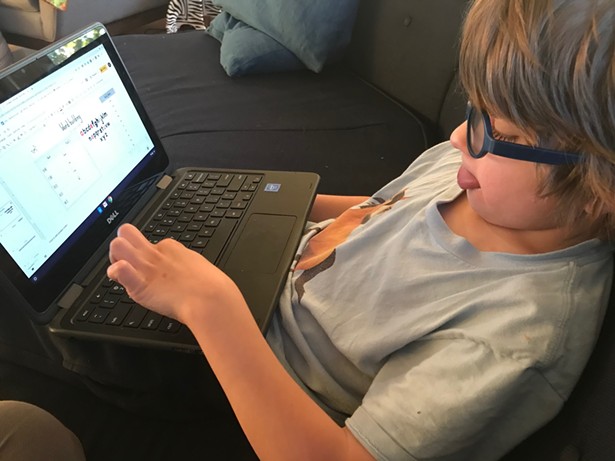

“This is way better, way less stressful,” says Maria Wetsell, mother of two kids including 14-year-old Will, who was diagnosed on the spectrum at the age of three. Wetsell is happy to be able to stay at home with her kids, and her son being out of the classroom has relieved some pressure. “The school environment is really hard for him. He is super-sensitive, super-hyper, super-smart,” she says, adding that Will displays more on the Asperger side of the spectrum and doesn’t require the same intensive engagement that other students might.

Like many students—not just those who have a developmental disability—the transition from attending courses to having to take classes at home has been difficult. Compartmentalizing is important for those on the spectrum—keeping to tight schedules and having specific spaces for specific activities can help ground those on the spectrum to what they should be focused on. It did take Will some time to ease into bringing school home with him, but in many ways the classroom environment presented more distractions for him.

“He struggles in the school environment, he struggles with his peers, he struggles with putting value on tasks,” Wetsell says. “If he already knows the work and already has an understanding of it, he’ll struggle with why he needs to show the work. He has a hard time motivating himself to do things he doesn’t value.”

With his coursework now held online and in a more concise format, Will’s motivation for school has improved. Wetsell attributes this success to strong communication with Will’s teachers about their expectations and modifying his IEP under the current conditions.

“Will’s teacher has been really incredible with this transition,” says Wetsell, though she does admit that the online learning doesn’t replace the benefit of Will being in class with his teacher. “He literally focuses the entire time on tasks, responds to questions, has great conversations. He does a lot of learning in this way.”

While online learning has been ideal for students like Will, many parents feel that their children’s education has lost the individual touch. Families have reported that much of the work their teachers send home feels like busy work, packets of worksheets and exercises to perform in lieu of the hours spent in class.

“I like school, but homeschool, I don’t really like that much,” says 9-year-old Sam Kolt, a fourth grader in the Arlington Central School District who is on the autism spectrum. “It’s all frustrating for me and stuff. Instead of doing school at home. It feels like I’m doing tons of homework and I don’t like that.” Melissa, his mother, agrees, but has additional concerns from any parents standpoint of bearing responsibility for their children’s progress.

“I’m concerned that he’s not going to get everything he needs to know,” says Kolt. “For instance, I’m supposed to be teaching him fractions. I feel like I’m not good enough at teaching him that, and a lot of things are built on that education. My concern is that the building blocks, the foundations aren’t going to be solid enough for him to get topics later on that builds from it.”

What Will the Future of Education Look Like?

When Governor Cuomo originally announced that school programs would remain online for the summer, he also gave notice that the state would issue guidelines in the beginning of June for schools and colleges to begin the process of planning and preparing how they envision reopening their facilities for the fall. These plans would then be submitted by a July deadline where the proposals would either be approved or denied. Whatever the case may be, going back to normal may not be an option.

“When you sit and think about it, we don't know what normal is going to be,” says Caren O’Brien-Edwards, the director of community services for Greystone Programs, a nonprofit organization that provides essential services and support for people with autism and other developmental disabilities in the Hudson Valley. One of the projects that she oversees is Greystone’s after-school program, which has been placed on pause since the pandemic. After strategizing multiple potential scenarios for reopening, O’Brien-Edwards says that Greystone is ready to go but is waiting on official approval.

“The only thing that would really probably change for us would be numbers in terms of how many people could come to a program,” O’Brien-Edwards says. “We have our plans in place, we have our supply lists in place, we have everything in place. Now we’re totally at the mercy of the state once they give us guidance.”

In addition to preparing how they will have to operate their programs in the days, months, or even years ahead, Greystone Programs is also doing what it can to help prepare the people it supports for the new normal, who may not necessarily understand social distancing and why it’s important to adhere to the guidelines.

“It’s hard, because it’s your natural reaction to go up to your friends or the people you care about and want to go give them a hug,” O’Brien-Edwards says. Using social stories and role-playing exercises are a few of the ways that Greystone Programs is passing on the concept of social distancing to the people it supports. However, not all the measures are as easily accomplished through storytelling. Explaining why everyone should wear masks doesn’t make wearing them any easier for those who have sensory boundaries.

“Wearing a mask is very invasive for a lot of the people we support,” O’Brien-Edwards says. “So we’re slowly desensitizing them by getting them used to wearing a mask. Having them wear a mask in their house for maybe one minute at a time. And then, moving up to maybe two minutes or three minutes and just trying to get them used to that, because if that’s going to be the way we need to go out into the community by wearing a mask, then you know that we want the people that we support to be prepared.”

As of the time of this reporting, Pharaoh’s school, like many across the state, has opted to continue providing its extended-school-year services online. While Cannon is not impressed by the efforts BOCES has put into remote learning and support for its students, the reality of being her son’s educator for the summer is daunting.

“It’s not like caring for a neurotypical child where I could just say, ‘Here’s your homework, call me when you need help.’ That's not how it works. I am literally having to be on top of him,” she says. As challenging as the past few months have been and as the immediate future looks, Cannon remains resilient, seeking to face the future with a smile rather than a grimace.

“I’d rather laugh than get frustrated, and that’s something I want to teach my son,” she says. She has a message for other parents facing the same struggles: “Laugh, laugh when you can. When you can make it silly, make it silly for you and your child to make it into a positive experience.”

While parents may have adopted an additional teaching role, that doesn’t mean they have to submit to the notion that they are living in a classroom. “Set boundaries for you and your child,” Cannon says. “It’s important to maintain as much normalcy as possible, and I’m not talking about normal normalcy. I’m talking about home normalcy. Because home should be the safe zone.”